As a Women’s and Gender Studies major, I’m lucky enough to have my class requirements align with the subjects I find most thought-provoking and applicable to my everyday life. In particular, a course called “Comparative Feminisms” offered me the opportunity to explore my existing understandings of the ongoing feminist movement, through a lens other than that which I so often see feminism filtered. Specifically, this class addressed the multi-faceted nature of black womanhood — the triumphs and the tribulations, the progression and the oppression, the collaboration and the dissonance — and let me tell you, their evolution is truly mind-blowing.

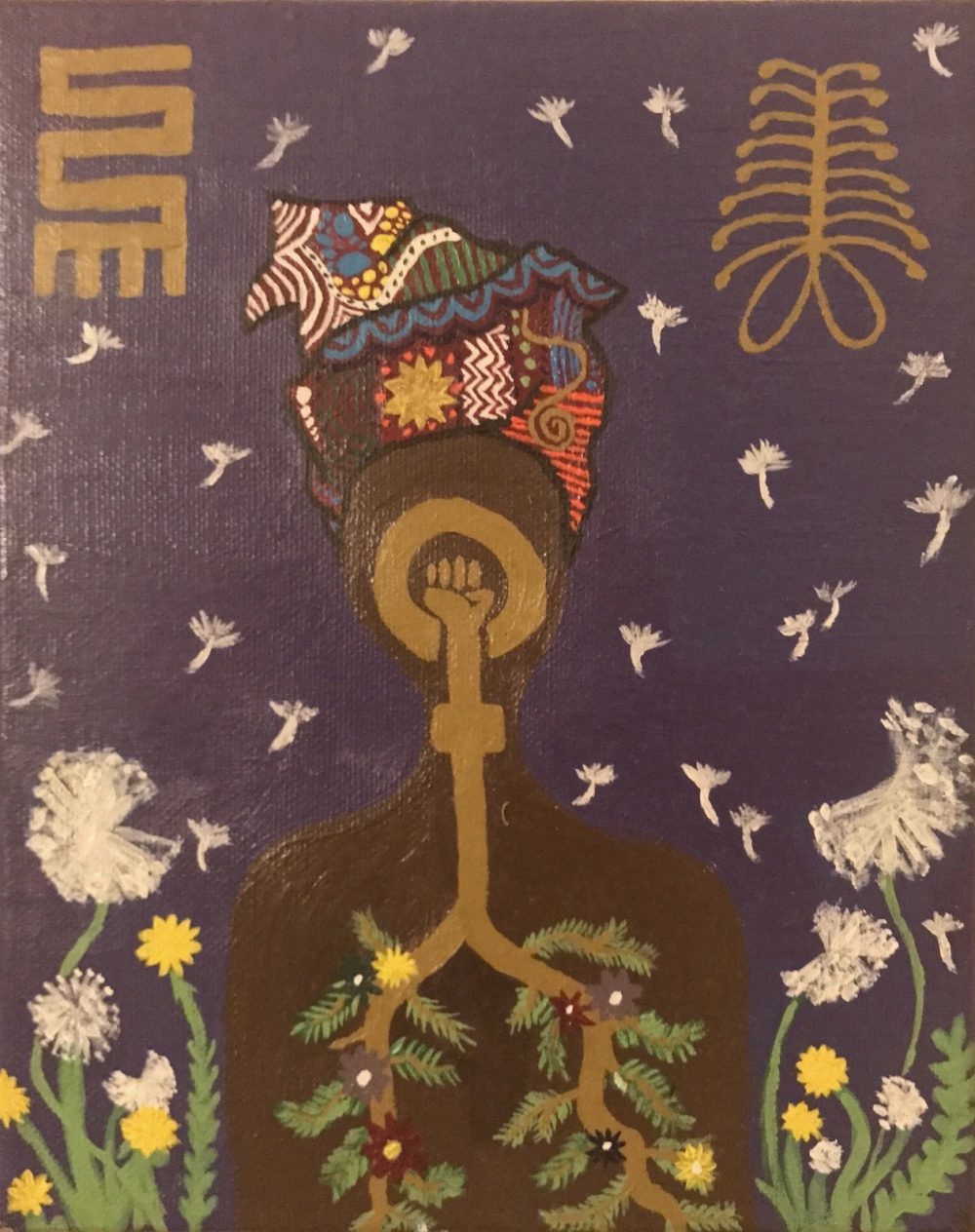

Through this painting, I sought to illuminate the many undusted, overlooked corners of their lives. I chose to do so because, as history has taught us, white supremacy, the patriarchy and mainstream feminism have not, in the many years of their existence, created this discourse themselves.

Notable Black scholar Alice Walker made the statement: “womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender,” which speaks directly to this reality. Just as lavender is a whitewashed form of purple, feminism is a whitewashed form of womanism — lacking the necessary strength, conviction, and intersectional consideration necessary to subvert white tyranny.

Racism, despite originating from and being perpetrated by white people, is constantly made to be a black person’s problem. Similarly, sexism, despite its male perpetrators, is constantly made to be a woman’s problem. This blatant disregard for the oppressed is only amplified when you consider the overwhelmingly constricted position of the black woman.

A term I grew quite familiar with during this course was “triple oppression” — a layered cake of sorts — that identifies black women, unlike their black male and white female counterparts, as being very uniquely troubled by the simultaneous classist, sexist, and racist public structures that have been so deeply embedded into our society.

Subsequently, the unrelenting “triple oppression” they face as a condition of existing in such socially imbalanced spaces, only serves to complicate their ability to self-identify and evolve in positive, meaningful ways. Hopefully, in my discussion of the work I have produced, I can more effectively articulate just how meaningful black women really are.

This class truly revealed the sheer magnitude of the African diaspora. Hordes of people were removed from their homeland against their will to be tortured, violated and unjustly forced into submission; an egregious act and an obvious breach of morality. Unfortunately, this act was so far-reaching and so integral to the history of developed nations that the lingering, racially-charged social dynamic has effectively pushed blackness to the very bottom of the social totem pole.

I often liken American blackness to little kids who’ve just been given a new puppy. The initial fascination is compelling; admiration of the fur, excessive ogling and touching (often to the point of roughness), and attempts to establish trust (which is really an attempt to assert dominance and establish power relations).

As black individuals, we are the puppies of society. Our bodies and our culture are endlessly fetishized: the cosmetic surgeries to enlarge body parts, the superficial adoption of black vernacular, the appropriation of our skin for the sake of Halloween/on-screen costumes, the list goes on. This non-black tendency to cherry pick bits and pieces of black culture for one’s own personal gain has become an increasingly blatant attempt to dwarf the black experience.

Eventually, the fascination with the puppy turns to irritation, and the irritation turns to exasperation. But unlike our non-black counterparts who can so easily walk the puppy back to the kennel and wash their hands of their appropriated blackness, individuals who are actually of African descent cannot escape their natural pigmentation and the structurally oppressive forces that are attached to it.

This is why, in the top right and left hand corners of my painting, you will find two Adinkra symbols. These symbols are West African borne and hold a variety of culturally significant meanings. The symbol on the left, “Nkyinkyim,” symbolizes “initiative, dynamism, and versatility” (Koutonin). These traits are very much linked to black livelihood, especially for black women considering their aforementioned triple oppression.

Despite having been ripped from their place of origin and thrust into a completely foreign and torturous space, black women and men code shifted to adapt to their changing environments. Their versatility has transcended the slave era into the modern day, and they continue to thrive in spite of their subjugated circumstances. For this reason, I intentionally left the woman faceless. This was done not to detract from her identity, but rather to speak to its complexity.

Firstly, as previously mentioned, the burden of relieving oppression never fails to fall on the shoulders of the oppressed. So, Black women (and men, to a lesser degree), in order to secure their survival and the survival of their loved ones, were forced to negotiate their identities for the sake of white America.

They didn’t like the way she spoke, so she changed her pitch and hardened the pronunciation of her “R’s”; they didn’t like the way she looked, so she bought new clothes and straightened her hair. While the constant need to code shift effectively compromised the black woman’s ability to live her truth, it was (and still is) the cost of survival in primarily white spaces.

Secondly, she is faceless because the black woman has no singular face — she assumes many different forms. Though many African American women struggle to identify their true ethnic origin (as a result of the cruel, yet effective, slave-owning tactic to separate families and tribes from one another), other black-identified women are adamant in their appreciation of their native cultures. But regardless of their ethnic, socioeconomic or religious background, each and every woman of African descent is of great worth and is fully deserving of a seat at the table.

On the right is the symbol “Aya,” signifying “endurance and resourcefulness”; yet another set of traits black individuals had to adopt as a mechanism for survival (Koutonin). After all, as the puppies of society, we often find ourselves underfoot. Thus, it becomes vital for us to possess the necessary stamina to not only keeps ourselves from being stepped on, but also to equip us with the emotional strength needed to endure the public’s fluctuating response to our presence. My use of these symbols is both an appreciation of West African culture itself and the principles it advocates, as well as a celebration of the individuals of African descent around the globe who, whether they know it or not, act as exemplars of these symbols.

The last component of this painting is the presence of the dandelions. Common understandings of dandelions would have us believe they are just a pesky invasive species that are only good for plucking and making wishes, but this is far from the case. Even though dandelions are technically considered an invasive species (a result of having been brought to North America via European settlers), they have an abundance of medicinal uses, some of which include: “[treating] kidney disease, swelling, skin problems, heartburn, and upset stomach…appendicitis, and breast problems, such as inflammation or lack of milk flow” (Ehrlich).

Much like the dandelion, black women and men were transported to a new world by Europeans seeking profit. And much like the dandelion, black women and men were/are constantly being told they lack value, or more simply, that they are “weeds”— a common misconception that was likely conceived in the white man’s attempt to dehumanize and denigrate black bodies.

It cannot be denied that white supremacist thought has effectively brainwashed people of African descent into internalizing this hatred, but time has given these individuals the opportunity to resist, unlearn and transform the way they see themselves in relation to white bodies. Much like the dandelion, black people are resilient and are overflowing with highly valuable qualities that could very well prove beneficial to society. It is up to society, however, to see the dandelion as more than just a “weed” waiting to be plucked.

Sources:

Ehrlich, Steven D. “Dandelion.” University of Maryland Medical Center. UMD, n.d. Wed. 19 Dec. 2016.

Koutonin, Mawuna Remarque. “63 African Symbols For Creative Design.” SiliconAfrica. Reklama, 4 June 2014. Web. 19 Dec. 2016.